Roundtable Roundup: Graft-vs-Host Disease

In separate live virtual events, Pashna N. Munshi, MD; Navneet Majhail, MD, MS; and participants at the respective discussions considered treatment options for a patient with chronic graft-vs-host disease (GVHD) after multiple previous treatment attempts.

CASE SUMMARY

A 48-year-old man underwent a myeloablative conditioning regimen for acute myeloid leukemia (AML), with tacrolimus (Prograf) plus methotrexate (Trexall) as GVHD prophylaxis. The transplant donor was a cytomegalovirus-seropositive 50-year-old woman with 3 children.

On day 22 following transplant, the patient developed acute GVHD of the skin, which was successfully treated with slow steroid taper. Bone marrow testing performed at 3 months posttransplant showed his AML was in complete remission.

At 6 months posttransplant, the patients’ blood counts were normal. However, he had skin changes with hyperpigmentation; approximately half of each arm showed lichen planus and superficial sclerotic features (able to pinch the skin) on the lower trunk and lower extremities. Eighteen-percent body surface area (BSA) was involved, and there was no decrease in forced expiratory volume in 1 second and carbon monoxide lung diffusion capacity on his pulmonary function tests.

Prednisone was initiated at 0.5 mg/kg per day, followed by a 4-week taper. After 7 days of prednisone, the patient had an initial improvement in BSA involvement. During the taper, however, there was an increase in BSA involvement from 15% to 20%. A subsequent taper was attempted unsuccessfully. Symptoms remained stable thereafter on 0.5 mg/kg every other day.

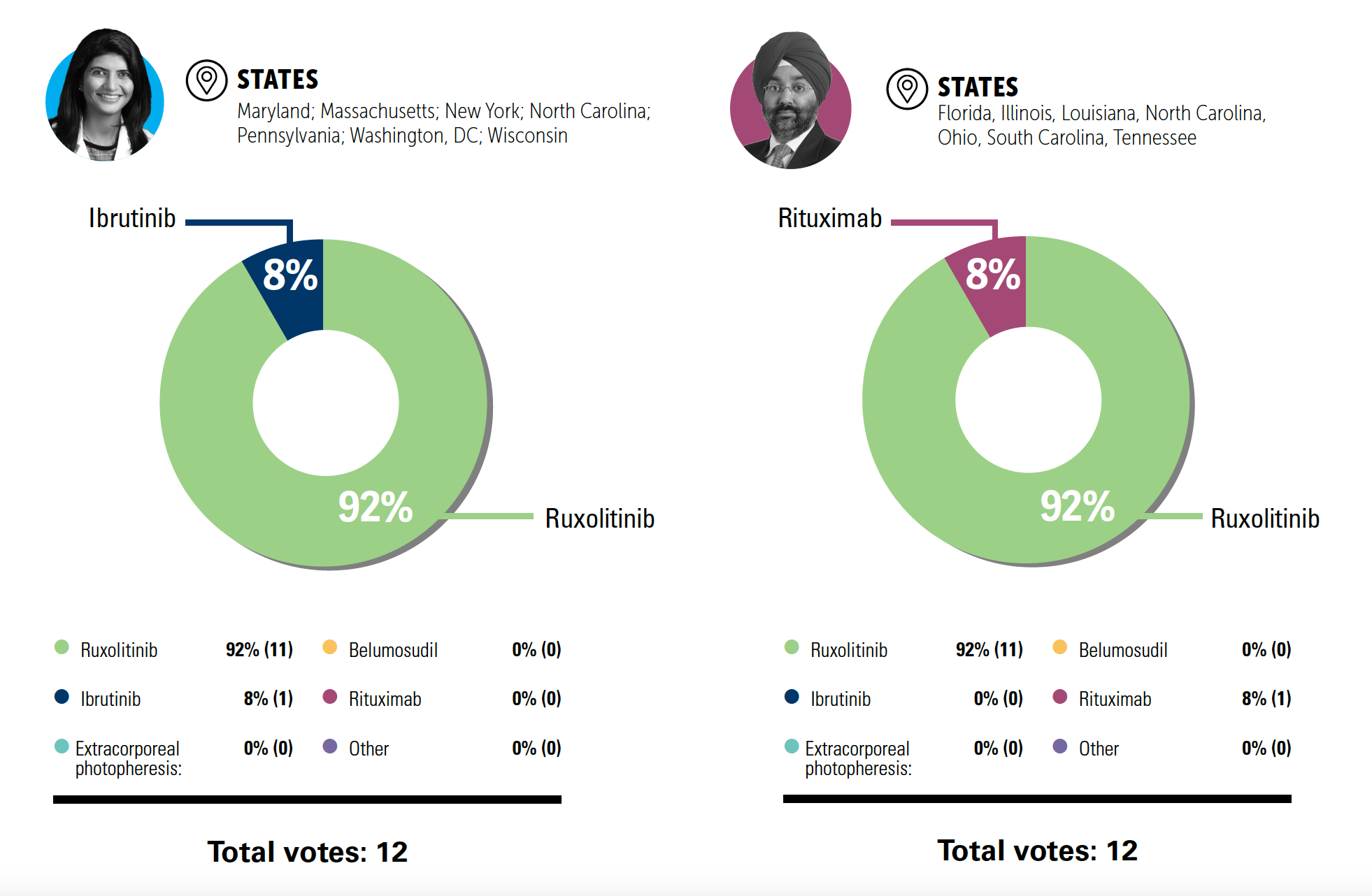

POLLING QUESTION

A decision was made to initiate additional therapy. Considering available clinical trial data, what would be your preferred therapy for a patient like this with steroid-dependent chronic GVHD?

Pashna N. Munshi, MD

Assistant Professor of Medicine

Georgetown University

Associate Clinical Director

Stem Cell Transplant and Cellular Immunotherapy Program

MedStar Georgetown University Hospital

Washington, DC

PASHNA N. MUNSHI, MD: If this patient had other organ involvement—gastrointestinal tract, lungs—we’re now moving on to severe chronic GVHD; clearly, we want to add something else. Is everyone in agreement on that?

COLLEEN DANIELSON, NP: [For severe chronic GVHD], I still add ruxolitinib [Jakafi], but I think about localized therapy, especially with high involvement. Our eye colleagues often use punctal occlusion or punctal plugs to help with eye symptoms. For the genitourinary [GU] tract, we think about other additional, more localized or topical therapies. I’d still use ruxolitinib up front as my second-line agent.

NANCY J. BUNIN, MD: We’ve used dupilumab [Dupixent] with ruxolitinib for some patients with chronic skin GVHD, and we’ve had some good responses with dupilumab. We send patients to dermatology because they get the approval for it, which can take a couple weeks. It’s given every 4 weeks, although…we’ve moved it up to every 3 weeks [for a couple pediatric patients]. It usually doesn’t work immediately; it usually takes a couple doses. But we’ve been very pleased with responses for many of the pediatric patients with skin GVHD, and it’s minimally toxic except for the injection, which parents give…. We’ve had pediatric patients getting both ruxolitinib and dupilumab, [and we’ve] been able to get them off ruxolitinib, keep the dupilumab, and then eventually stop the dupilumab because their GVHD is gone.

COLLEEN DANIELSON, NP: I see women with gynecological involvement. We use topical clobetasol [to treat them], and I’ve had great responses with that. Women also often need topical estrogen for tissue changes and estrogen deficiencies that correlates with their chronic GVHD.

NANCY J. BUNIN, MD: For lung involvement, the pulmonologist put them on [fluticasone, azithromycin, and montelukast] in addition to ruxolitinib. Pediatric patients are also seen by pulmonology. There’s a prospective study monitoring pulmonary function tests on allogeneic patients. But in patients with bronchiolitis obliterans, they do get additional therapy with azithromycin and inhaled steroids.

Navneet Majhail, MD, MS

Physician-in-Chief of Blood Cancers

Sarah Cannon Transplant and Cellular Therapy Network

Program Medical Director

Sarah Cannon Transplant and Cellular Therapy Program

TriStar Centennial Medical Center

Nashville, TN

NAVNEET MAJHAIL, MD, MS: What if this patient was steroid refractory or intolerant instead of steroid dependent?

MOHAMED A. KHARFAN DABAJA, MD, MBA: With the availability of all these new therapies—whether it’s ruxolitinib, belumosudil [Rezurock], extracorporeal photopheresis, or others—I don’t think the refractoriness vs the dependence makes sense anymore. We don’t rechallenge them to prove they’re steroid [refractory or dependent]. If I see there’s lack of response or inability to taper, then I move on to second line. Sometimes I even add ruxolitinib, or whatever you decide to add, without waiting for the fatal [issue] to manifest itself. The gray zone between refractory and steroid dependent is becoming less relevant in the daily practice, in my opinion.

SYED A. ABUTALIB, MD: I agree with you, [and I would] do the same. But I’m less nervous when it’s intolerant when I’m using ruxolitinib, as they’re most likely to respond [than] when they are refractory, in terms of prognosis. I do not know [whether] they have looked at this in a retrospective study, whether intolerant is better than refractory. I think patients with [an intolerance] would do better because they are responding, or they’re just intolerant as opposed to more stubborn disease.

NAVNEET MAJHAIL, MD, MS: That’s a good point, and I would agree with you. If somebody is responding but is not able to tolerate steroids, [they] would have a higher chance of responding to second- or third-line therapies vs someone who is progressing on steroids. I’m not sure off the top of my head of any data that support that, but just from an anecdotal clinical perspective, I would agree with you.