Mechanism-Driven Science Informs Novel Treatments in Soft Tissue Sarcoma

Various combination strategies are being explored in soft tissue sarcomas in efforts to increase efficacy.

Brian A. Van Tine, MD, PhD

Professor of Medicine

Division of Oncology

Section of Medical Oncology

Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis

St. Louis, MO

Breelyn A. Wilky, MD

Director of Sarcoma

Medical Oncology

The Cheryl Bennett and McNeilly Family Endowed Chair in Sarcoma Research

Deputy Associate Director for Clinical Research

University of Colorado Medicine

Aurora, CO

Data from a number of studies showing impressive efficacy vs historical efficacies in soft tissue sarcomas (STS) caused both Brian A. Van Tine, MD, PhD, and Breelyn A. Wilky, MD, to say, “It's an exciting time to be a sarcoma doctor,” in separate interviews with Targeted Therapies in Oncology. They were describing results presented at the 2023 American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) Annual Meeting. Van Tine, a professor of medicine and sarcoma program director at Washington University School of Medicine in St Louis, Missouri, explained that the field is moving toward mechanism-driven science, with preclinical exploration of the biology of STS, including immune system biology and genomics, informing clinical trials. “We’re no longer just throwing darts at a board,” he said.

Various combination strategies are being explored in STS in efforts to increase efficacy.1 For example, immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs), which previously have shown only modest activity in STS as monotherapies,2,3 were combined with chemotherapy, resulting in improved activity. “ICIs had shown modest efficacy in STS, really less than about 20%. And so, there has been this huge effort to combine ICIs with chemotherapy or targeted therapies to try to improve responses for more patients,” Wilky, director of sarcoma medical oncology, The Cheryl Bennett and McNeilly Family Endowed Chair in Sarcoma Research, and deputy associate director for clinical research at the University of Colorado Medicine in Aurora, Colorado, said. The hypothesis is that the targeted agents and the chemotherapy can prime the tumors, allowing the ICIs to act afterward, explained Van Tine.

This was the case of the combination of nivolumab (Opdivo) with trabectedin as a second-line treatment of patients with anthracycline-pretreated metastatic or inoperable STS, which was evaluated in the German Interdisciplinary Sarcoma Group prospective phase 2 NiTraSarc trial (GISG-15; NCT03590210) and showed activity in patients with lipo- or leiomyosarcomas (LMS).3 At first, a late combination cohort (LCC) received 3 cycles of trabectedin alone, with nivolumab being added at cycle 4 for up to 16 cycles. Following positive results in a preplanned interim analysis, nivolumab was added from cycle 2 for patients in the early combination cohort (ECC). After a median follow-up of 16.6 months, the overall progression-free survival (PFS) rate after 6 months was 47.6% (60% in LCC vs 36.4% in ECC), with a median PFS of 5.5 months (9.8 months vs 4.4 months), and a median overall survival (OS) of 18.7 months (24.6 months vs 13.9 months).3

These results also suggest that a longer lead-in time with chemotherapy helps prime the tumor for immunotherapy. Immunogenic tumors, those with high numbers of tumor-infiltrated lymphocytes, and those with tumor- associated macrophages that actively modulate the immune response to survive—for example, by expressing immune checkpoint ligands that suppress the antitumor immune response—are called “hot” or “inflamed” tumors. Hot tumors are more likely to benefit from ICIs.4 The immune micro environment is highly variable in STS, with some subtypes having strong immune presence, which offers a promise for immunotherapy in those malignancies, whereas other subtypes are classified as “cold” tumors.4

Another nivolumab and chemotherapy combination was evaluated in the phase 1/2 ImmunoSarc2 trial (NCT03277924), in which 2 chemotherapy agents were used: doxorubicin and dacarbazine.5 Anthracycline-naïve patients with advanced/metastatic LMS received up to six 21-day cycles of the triplet, followed by 1 year of nivolumab maintenance. This regimen was well tolerated, with investigators observing no dose-limiting toxicities. Grade 3 to 4 adverse events (AEs) included neutropenia, anemia, febrile neutropenia, asthenia, and increased γ-glutamyltransferase levels. With a median follow-up of 8 months, 15 of 20 participants remained on the therapy (9 with partial responses [PRs] and 6 with stable disease), and the median PFS was 8.67 months.5

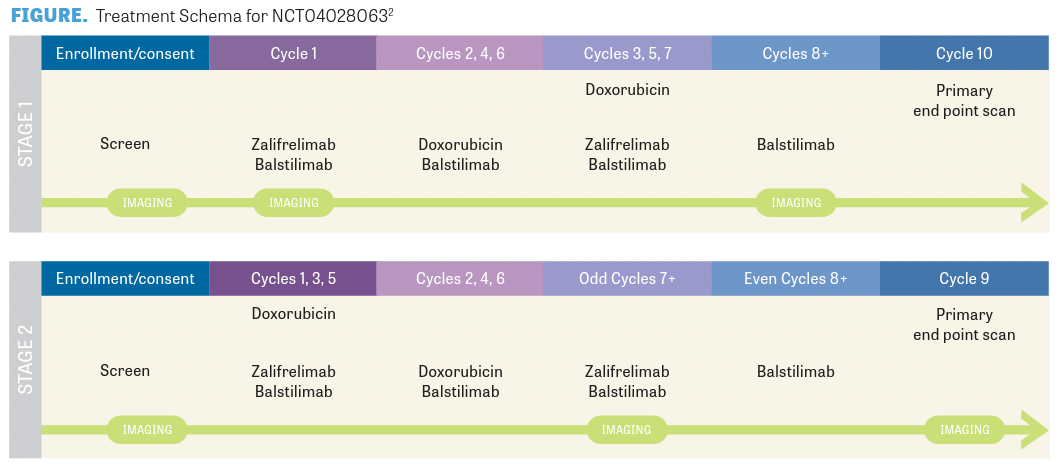

Wilky presented results from a single-arm phase 2 trial (NCT04028063; FIGURE2) with another combination of chemotherapy, doxorubicin, this time with the ICIs zalifrelimab (anti–CTLA-4) and balstilimab (antiPD-1).2 “What we saw was that [approximately] 36% of patients had a response, with 86% having disease control. We saw responses in immune hot sarcomas, like angiosarcoma and pleomorphic sarcoma. But we were excited to also see responses in patients that we weren’t expecting [to, such as] a patient with endometrial stromal sarcoma,” Wilky said. These results suggest that priming with chemotherapy allows ICIs to effectively target “cold” STS, confi rming previous preliminary results.2

Wilky emphasized that “we don’t really know how to sequence these therapies for STS yet.” It is not clear whether to start the chemotherapy or the ICIs fi rst, or even whether clinicians should give them together from the start. Different studies are showing different results. It is important to keep in mind that these are very small studies. “ There was a lot of discussion about [the results]—is it the treatment that did it or was it just the patients [who] were selected? It’s going to take a lot more analysis of patient samples as well as modeling in the laboratory and mice models to sort through all that.”

These challenges highlighted by Wilky are in part due to the fact that STS are rare, with only approximately 13,500 new cases reported in the United States in 2021, representing an incidence rate of 15 to 35 per 1 million of the adult population, which accounts for only 1% of all adult cancer diagnoses.6 Moreover, STS represents a heterogeneous group of tumors of mesenchymal cell origin that can occur anywhere in the body.6 The implications of this diversity are clear in the varying results discussed here. The rarity and the heterogeneity contribute to the challenges faced by experts in the field, a fact that both Wilky and Van Tine highlighted.

Another chemotherapy and ICI combination tested was that of doxorubicin with a novel ICI, TTI-621. This recombinant fusion protein combines the Fc region of human IgG1 with a fragment of human SIRPα and is designed as a decoy receptor for CD47 on tumor cells to interrupt CD47-SIRPα signaling and promote macrophage-mediated phagocytosis of tumor cells, as well as the activation of natural killer cells.7 Evidence from preclinical studies suggests that TTI621 may enhance the response to doxorubicin in macrophage-rich tumors that express CD47, such as LMS. This open-label study evaluated TTI-621 and doxorubicin in anthracycline-naïve patients with unresectable or metastatic high-grade LMS and 1 or 0 prior lines of therapy for advanced disease. The combination showed promising clinical activity and a favorable safety profi le among patients with advanced LMS, including those with prolonged exposure to TTI-621.7

Two more combination strategies were also presented at ASCO 2023: the combination of immunotherapies with targeted agents8 and the combination of chemotherapy with targeted agents.1,9

Van Tine presented data on the combination of the targeted agent cabozantinib, a tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) with dual activity against VEGF and c-MET, with 2 ICIs, nivolumab and ipilimumab.8 “This combination has been tested across many other solid tumors and we were fortunate enough to be allowed to see if this combination would actually work in STS,” explained Van Tine. “I think we’re beginning to see that there is a signal, especially, a signal that immunotherapy should be pursued for a specific kind of sarcoma, LMS, which is traditionally not thought to be a very immunotherapy-sensitive tumor.” Additionally, the study findings showed a sizable shift in the disease control rate when immunotherapy was added to cabozantinib (80%) compared with cabozantinib alone (42%).8 Van Tine commented that “this was a huge shift” and “we need to learn more about what’s going on, because now we actually have comparators.” He added that they are also seeing disease control lasting up to 2 years, which is a long-term benefit that had not been seen before. “It’s a big step forward that we can do these trials in sarcoma in a randomized way.”

“We have a lot of trouble in our field interpreting [data from] many of our single-arm studies. I’m hoping this study sets a paradigm for how we move forward. This should be the new model for how we interpret [data from] our smaller studies, because we need some concurrent control arms that will tell us where our signals are,” explained Van Tine.

Preclinical and clinical data have shown that the combination of antiangiogenic agents and chemotherapy results in a synergistic effect. Therefore, a multicenter phase 2 study explored the effectiveness and safety of combining temozolomide, an alkylating chemotherapeutic agent, with cabozantinib in patients with unresectable/metastatic LMS and other STS.1 The primary end point was progression-free rate (PFR) at 12 weeks for cohort 1 (uterine and nonuterine LMS), which was 45.9%, with a median PFS of 6.4 months. This exceeds the primary end point with a 12-week PFR greater than 39%, and the PFS exceeds rates achieved with second-line TKIs and alkylators in patients with LMS. Additionally, the objective response rate (ORR) was 13.5% with 5 PRs. For cohort 2 (other STS), the 12-week PFR was 50% with a median PFS of 3.2 months and 1 PR. Treatment with cabozantinib plus temozolomide was feasible and did not reveal any previously unreported toxicities. Common grade 3 to 4 AEs included hypertension, decreased neutrophils, and decreased platelets.1 Cabozantinib plus temozolomide demonstrated meaningful clinical benefit and is worth further exploration in LMS.1

Another phase 1b trial evaluated the combination of doxorubicin with lurbinectedin, a selective inhibitor of oncogenic transcription that binds preferentially to guanines located in the GC-rich regulatory areas of DNA gene promoters.10,11 This is used for the treatment of patients with locally advanced or metastatic, unresectable nongastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST), without prior exposure to anthracycline or lurbinectedin/trabectedin.9 Half the patients (5 of 10) remain on treatment with a median PFS of 357 days, after a median follow-up of 344 days. All but 1 patient either responded (PRs, 6 of 10) or had stable disease (3 of 10) with 81 days as the median time to PR, and the duration of response was over 132 days for all responders, with 3 still on treatment. The toxicity profile was as expected for each agent with no new AEs reported.9 A randomized phase 2 trial is currently enrolling participants.

Single Agents

TKIs are also used as single agents for the treatment of STS. For example, surufatinib, a multitargeted, small molecule TKI with strong inhibitory effect on the activity of VEGFR-1, -2, -3, FGFR1, and CSF-1R, was well tolerated and showed some clinical activity in patients with advanced osteosarcoma and STS for whom standard chemotherapy was not effective.12

Neoadjuvant Setting

The feasibility and activity of concurrent chemotherapy, epirubicin and ifosfamide (Ifex), and radiation therapy (RT) in the neoadjuvant setting for patients with localized, high-risk STS was evaluated in an international, randomized phase 3 trial (ISG-STS 10-01; NCT01710176).13 RT was delivered according to clinical judgment either preoperatively (concurrent with chemotherapy; 146 patients) or postoperatively (143 patients). There were no statistical differences between the 2 groups in terms of toxicities; however, the concurrent group did have a higher number of surgical postoperative complications. Importantly, concurrent chemotherapy and RT resulted in a statistically higher response rate than postoperative RT. This combination may help when tumors are of borderline resectability or when function preservation is a goal.13

Other Promising Agents

In addition to the promising results presented at ASCO 2023, results for other agents that were not discussed in the meeting have recently been published. This was the case for the combination of TQB2450, a novel PD-L1 antibody, with anlotinib, a multitarget TKI, against tumor angiogenesis and tumor cell proliferation that acts by targeting VEGFR, FGFR, platelet-derived growth factor receptor, and c-Kit simultaneously.14-16 This combination showed promising activity, particularly in patients with alveolar soft part sarcoma, among whom it demonstrated an ORR of 75% and a median PFS of 23.06 months, with tolerable toxicity.17

LB-100 is a first-in-class, small molecule inhibitor of protein phosphatase 2A. In preclinical studies, LB-100 inhibited the proliferation of cell lines from a variety of tumors and potentiated the activity, without significantly increasing the toxicity of cisplatin, doxorubicin, and temozolomide against xenographs of various tumors. It also reversed resistance to cisplatin in various tumor xenographs.18 In an open-label, dose- escalation, phase 1 study, in which investigators administered LB-100 for 3 consecutive days to patients with progressive solid tumors for whom standard treatments had not been successful, half the patients had stable disease for 4 or more cycles and 1 patient had a PR after 10 cycles that was maintained for 5 additional cycles.18

Future Directions

“It’s just nice to see sarcoma finally catching up a little bit and seeing some of this emerge because we’re so far behind other cancers due to the rarity and the heterogeneity of STS,” said Wilky. “We’ve shown through these studies that we can do randomized clinical trials, like the cabozantinib plus ipilimumab [Yervoy] and nivolumab study. We can do that in STS, and we can do it pretty quickly and get good data. So it’s really encouraging for the field.”

Both Wilky and Van Tine expressed excitement about the future of the field of STS, with real opportunities to benefit patients and move drugs along the pipeline. However, “there’s a lot more work that needs to be done. The field is starting to divide up our hotter tumors from our clearly colder tumors,” said Van Tine, adding that there is a need for future clinical trials to figure out which patients should be matched with which agents. Wilky echoed this, adding that “we’re in a really exciting time and as the data move forward, as long as we are taking the care to analyze the patient samples and the models in the lab, we’re going to see our understanding improve over the next couple years.”